| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

Unifying the Plots of Shakespeare's A Midsummer-Night's DreamFrom Shakespeare's Comedy of A Midsummer-Night's Dream. Ed. Katharine Lee Bates. Boston: Leach, Shewell, & Sanborn.From one point of view A Midsummer-Night's Dream is a triumph of construction. The most heterogeneous fowl, — a classical hero, a Teutonic goblin, an Amazonian queen, grotesque English artisans, two brace of Athenian lovers, and the daintiest woodland fairies that ever sang lullaby with Philomel, are caught together in a moonshine net of poetry spangled with allusions to mythical demigods, mediaeval nuns, Warwickshire mayers, London actors, Indian kings, French coins, Centaurs, sixpences, the Man in the Moon, Bacchanals, heraldry, Jack and Jill, mermaids, magic herbs, swords, guns, Tartars, and the Antipodes. The elfin queen of subjects so tiny as to "Creep into acorn-cups and hide them there"winds in her arms the big body of a human clown. Four days so quickly steep themselves in nights, four nights so quickly dream away the time, that not all the counting of all the critics has yet righted the silver striking of the fairy clock. The waning moon is full before she is new. The play that is acted in the palace has forgotten the parts assigned in the carpenter's shop and the speeches rehearsed in the grove. The threat of death excites Hermia far less than the slur on her stature. Fairy sentinels nod at their posts, and the asshead enables Bottom to speak the English tongue. It ought to be all a jumble, and it is an artistic harmony. But how? What, in this that looks so helter-skelter, is the unifying truth? Here the scholars are at variance. The play is a twist of gold cord and rainbow silks, homespun yarn and shimmering moonbeams. The royal gold, it is generally agreed, binds the rest together, but does not make a part of the actual comedy-knot. Each of the other threads in turn has felt the critical tug.

"We hurry over the tedious quarrels of the lovers," declares Mr. Marshall (Irving Shakespeare, 1888), "anxious to assist at the rehearsal of the tragi-comedy of 'Pyramus and Thisbe.' The mighty dispute that rages between Oberon and Titania about the changeling boy does not move us in the least degree. We are much more anxious to know how Nick Bottom will acquit himself in the tragical scene between Pyramus and Thisbe. It is in the comic portion of this play that Shakespeare manifests his dramatic genius."

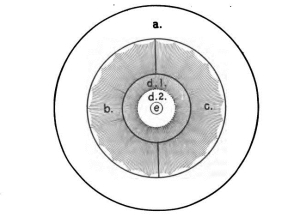

a. Theseus and Hippolyta. b. The Lovers. C. The Clowns. d. The Fairies, the "night-rule" of Titania (l) lying apart from that of Oberon (2).

e. The Magic Flower. "heads are hangIf we meet the duke between "after-supper and bed-time," he sits in the circle of the lights, smiling graciously as he classes in one category of "seething brains" "The lunatic, the lover, and the poet."He takes good-humored pleasure in the absurdities of the interlude, unaware that Shakespeare may be quizzing even him, to whom the Real is the all, to whom "strong imagination" is but a thing of "tricks," in the blundering efforts after realism manifested in Wall and Moonshine. Lysander and his sharp-tongued Hermia, Helena and her still enchanted Demetrius, touch prose-land on the side of their daily Athenian living; but their loves and their youth have made them free of the fairy-haunted wood for one long midsummer night.

As for Bottom, he is the very creature of delusion. Self-love lays a more potent spell upon the eyelids than the infatuation even of a Titania for an ass.

"This hateful imperfection of her eyes."Startled by the morning lark, away trip the fairies after the night's shade, — "We the globe can compass soon,and the hunting-horns of Theseus awake the lovers. This long-bewitched quartet, their parts tunefully adjusted at last, kneel before the duke for his urbane and easy pardon, and rise, with haunting memories of agonies and raptures gone, to make ready for their weddings. Even Bottom arouses from such a dream as "the eye of man hath not heard," and, with a marked lapse in his English, hurries on the play. The fifth act, like the first, opens in the realm, not of Oberon, but of Theseus — yet with a difference. The literalism of the players parodies the realistic theories of the duke, the "very tragical mirth" of the interlude mocks the forest adventures of the lovers, and possibly Bottom himself vaguely suspects derision in the plaudits. The world of fact is never so stable and serious again after a midsummer night in fairyland. And when, at last, "The iron tongue of midnight hath told twelve,"and the palace is hushed and dim, frolic trippings and warbled notes and glimmering sprites bless the bridal chambers, sweeping away the impurities of life's toilsome hours, and purging man's mortal grossness yet once more with the mysteries of moonlight, dreams, and love. How to cite this article:_____ Related Articles |

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.