| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

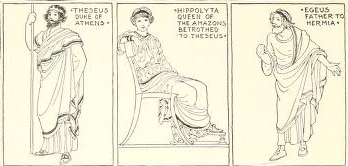

A True Gentleman: Examining Shakespeare's TheseusFrom Shakespeare's Comedy of A Midsummer-night's Dream. Ed. William J. Rolfe. New York: American Book Company.In dealing with the characters of the play, the first thing that attracts our attention is the extraordinary diversity of the groups, representing the extremes of human station and culture, together with the supernatural element in the fairies. "The heroic magnificence of the princely loves of Theseus and his Amazon bride," mingling classical allusion and fable with the ideas and manners of chivalry, is intertwined with the complicated errors and confusion of the Athenian lovers, due to the magic trickery of Oberon and Puck; and with this are blended the grotesque absurdity of the interlude — itself a burlesque of a romantic and tragic classical story — and the Athenian clowns who perform it. Never before or since were the sublime and the ridiculous, the heroic and the vulgar, the human and the superhuman, so exquisitely and effectively combined in a poetic symphony. The human characters of the better class are of minor interest, with the single exception of Theseus. As Dowden remarks, "There is no figure in the early drama of Shakespeare so magnificent"; but even Dowden, it seems to me, fails to do full justice to the finer traits of the hero. He calls him "gracious to all," and says that he "will not give unmannerly rebuff to the painstaking craftsmen who have so laboriously done their best to please him." The fact that he is a gentleman in the truest sense might well have been more emphasized. The negative reference to his acceptance of the clowns' interlude does not give due credit to the refined courtesy and consideration with which he welcomes their clumsy effort to do him honour. When Philostrate tells him how they have " toiled their unbreathed memories" to prepare the play, his prompt reply is, "Anil we will hear it." Philostrate says that really the thing is not worth listening to, unless perchance his lord " can find sport in their intents"; but Theseus replies:— "I will hear that play;And how admirably is this dwelt upon and impressed in the dialogue that follows:— "Hippolyta. I love not to see wretchedness o'ercharg'd,When, as the play is going on, Hippolyta pronounces it the silliest stuff she ever heard, Theseus says: "The best in this kind are but shadows; and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them." She replies, "It must be your imagination then, and not theirs"; but that is precisely what Theseus means. If the actor has not the imagination to enable him to realize the part, — to become for the time the character he personates, — let your imagination supplement his and complete his imperfect rendering. The best theatrical representation is more or less inadequate, and fails in a measure unless it sets the spectator's imagination to work to supply its deficiencies. In other words, "the dramatist must appeal to the mind's eye rather than to the eye of sense, and the cooperation of the spectator with the poet is necessary." Later in the performance, when Hippolyta expresses her weariness, Theseus replies: "But yet, in courtesy, we must stay the time"; that is, must see the thing through — "in courtesy," due, he implies, to the humblest no less than to the highest. He makes gentle fun of the poor stuff, but not, like Lysander and Demetrius, in a manner that might hurt the feelings of the thick-skinned actors; and at the close he tells them that their tragedy has been "very notably discharged." In all this, of course, it is Theseus that speaks, and not the dramatist in his own person; but the Theseus is Shakespeare's Theseus, not the hero of the old Greek myth or of any modern reproduction thereof. Would the poet have made him a true gentleman if he had not believed that the true hero should be a gentleman? And would this conception of the heroic character have occurred to one who was not himself a gentleman? Compare this Theseus with him of The Two Noble Kinsmen, who is at best only an heroic brute. He can fight for injured queens, and do great deeds for his own glory; but he has not a particle of the refined humanity that we see in Shakespeare's Theseus. The difference in the treatment of this one character in the two plays is, to my thinking, sufficient proof that they are not the work of the same author. I was once inclined to the opinion that Shakespeare had a hand in The Two Noble Kinsmen, but I do not now believe that he wrote a single line of it. The most impersonal of dramatists cannot entirely conceal his personality in his plays. The heart no less than the hand of the creator is inevitably revealed in certain of his creations. From what they are we know in a measure what he must have been. The "meanest of mankind," though he had been "the wisest, brightest" withal, could never have produced the Shakespearean Theseus, or Brutus, or Portia, or Imogen. Grapes are not to be gathered of thorns at St. Alban's or anywhere else. They do grow on various sorts of vines; but the Stratford grapes have an exquisite flavour that could come only from a plant of the finest strain. How to cite this article:_____ Related Articles |

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.