| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

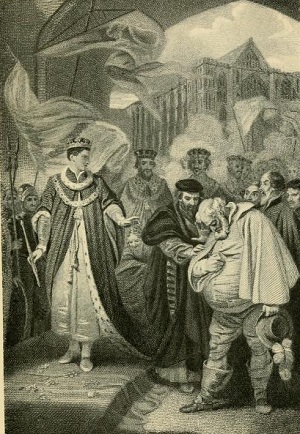

Henry IV Character IntroductionFrom Henry IV, First Part, by the University Society. New York: University Society Press.Sir John FalstaffHe [Falstaff] is a man at once young and old, enterprising and fat, a dupe and a wit, harmless and wicked, weak in principle and resolute by constitution, cowardly in appearance and brave in reality, a knave without malice, a liar without deceit, and a knight, a gentleman, and a soldier without either dignity, decency, or honour. This is a character which, though it may be decompounded, could not, I believe, have been formed, nor the ingredients of it duly mingled, upon any receipt whatever. It required the hand of Shakespeare himself to give to every particular part a relish of the whole, and of the whole to every particular part.Morgann: The Dramatic Character of Sir John Falstaff. ______ Falstaff is perhaps the most substantial comic character that ever was invented. Sir John carries a most portly presence in the mind's eye; and in him, not to speak it profanely, "we behold the fulness of the spirit of wit and humour bodily." We are as well acquainted with his person as his mind, and his jokes come upon us with double force and relish from the quantity of flesh through which they make their way, as he shakes his fat sides with laughter or "lards the lean earth as he walks along." Other comic characters seem, if we approach and handle them, to resolve themselves into air, "into thin air"; but this is embodied and palpable to the grossest apprehension: it lies "three fingers deep upon the ribs," it plays about the lungs and diaphragm with all the force of animal enjoyment. His body is like a good estate to his mind, from which he receives rents and revenues of profit and pleasure in kind, according to its extent and the richness of the soil. . . . He is represented as a liar, a braggart, a coward, a glutton, etc., and yet we are not offended, but delighted with him; for he is all these as much to amuse others as to gratify himself. He openly assumes all these characters to show the humorous part of them. The unrestrained indulgence of his own ease, appetites, and convenience has neither malice nor hypocrisy in it. In a word, he is an actor in himself almost as much as upon the stage, and we no more object to the character of Falstaff in a moral point of view than we should think of bringing an excellent comedian, who should represent him to the life, before one of the police offices. We only consider the number of pleasant fights in which he puts certain foibles (the more pleasant as they are opposed to the received rules and necessary restraints of society), and do not trouble ourselves about the consequences resulting from, them, for no mischievous consequences do result. Sir John is old as well as fat, which gives a melancholy retrospective tinge to his character; and by the disparity between his inclinations and his capacity for enjoyment, makes it still more ludicrous and fantastical. Hazlitt: Characters of Shakespeare's Plays. ______ Nothing can be less like the mere mouthpiece of an idea or the representative of a tendency than Falstaff, whose incomparably vivid personality is rather, notwithstanding his childlike innocence of mental or moral conflict, a very meeting-point of conflicting traits. But we can hardly be wrong in regarding as the decisive trait which justifies the extraordinary role he plays in this drama, his wonderful gift of non-moral humour. It is his chief occupation to cover with immortal ridicule the ideals of heroic manhood - the inward honour which the Prince maintains, a little damaged, in his company, as well as the outward honour which Hotspur would fain pluck from the pale-faced moon. His reputation is a bubble which he delights to blow for the pleasure of seeing it burst. He comes of a good stock, has been page to the Duke of Norfolk, and exchanged jests with John of Gaunt. But like the Prince, and like Hotspur, he is a rebel to the traditions of his order; and he is the greatest rebel of the three. Shakespeare's contemporaries, however, and the whole seventeenth century, conceived his revolt as yet more radical than it was, taking him, as the Prince does, for a genuine coward endowed with an inimitable faculty of putting a good face on damaging facts. Since the famous essay of Maurice Morgann criticism has inclined even excessively to the opposite extreme, conceiving him as from first to last a genial artist in humour, who plays the coward for the sake of the monstrous caricature of valour that he will make in rebutting the charge. The admirable battle-scene at Shrewsbury is thus the very kernel of the play. It is altogether a marvellous example of epic material penetrated through and through with dramatic invention; and Shakespeare's boldest innovations in the political story are here concentrated. Here the Prince reveals his noble quality as at once a great warrior, a loyal son, and a generous foe - in the duel with Hotspur, the rescue of his father, and the ransomless release of Douglas; - all incidents unknown to the Chronicles. Here Hotspur falls a victim to his infatuated disdain of the rival whose valour had grown "like the summer grass, fastest by night." And here Falstaff, the mocker at honour, lies motionless side by side with its extravagant devotee - not like him dead, but presently to conjure up the wonderful phantom of the fight for a good hour by Shrewsbury clock. Herford: The Eversley Shakespeare. ______ Shakespeare created a kind of English Bacchus at a time when every kind of fruit or grain that could be made into a beverage was drunk in vast quantities; and sack, which was Falstaff's native element, was both strong and sweet. Falstaff is saved by his humour and his genius; he lies, steals, boasts, and takes to his legs in time of peril, with such superb consistency and in such unfailing good spirits that we are captivated by his vitality. It would be as absurd to apply ethical standards to him as to Silenus or Bacchus; he is a creature of the elemental forces; a personification of the vitality which is in bread and wine; a satyr become human, but moving buoyantly and joyfully in an unmoral world. And yet the touch of the ethical law is on him; he is not a corrupter by intention, and he is without malice; but as old age brings its searching revelation of essential characteristics, his humour broadens into coarseness, his buoyant animalism degenerates into lust; and he is saved from contempt at the end by one of those exquisite touches with which the great-hearted Poet loves to soften and humanize degeneration. Mabie: William Shakespeare: Poet, Dramatist, and Man. How to cite this article: _________ Related Articles |

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.