| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

|

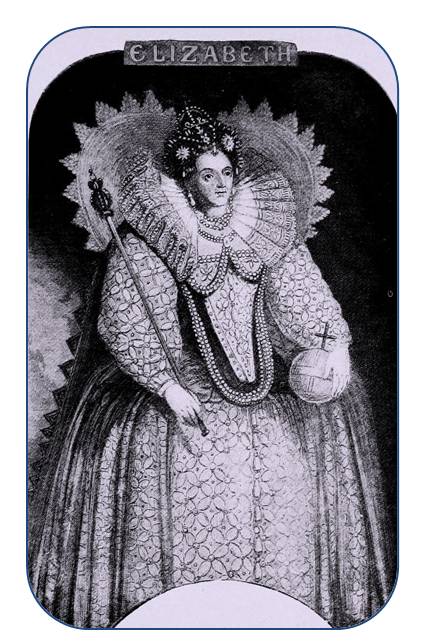

From The Elizabethan People by Henry Thew Stephenson: New York, Henry Holt and Company. One who would comprehend the style of Elizabethan dress must, for the time being, set aside all notion of simplicity or fit. In fact, the people of that time carried their idea of what was proper in wearing apparel to such a ridiculous extreme that they were made the subject of innumerable satires; and dress was the most popular point of attack by all the abusive writers on reform. Bright colours, elaborate trimmings, and excessive padding are the most notable characteristics of Elizabethan dress. Padding was so full that all outward semblance to the human form was completely lost, both to men and to women. "There is not any people under the zodiac of heaven," says Philip Stubbes, "however clownish, rural, or brutish soever, that is so poisoned with the arsenic of Pride or hath drunk so deep of the dregs of this cup as Alga [England] hath." Harrison, a contributor to Holinshed's history, wrote: "The phantastical folly of our nation (even from the courtier to the carter) is such that no form of apparel liketh us longer than the first garment is in the wearing, if it continue so long, and be not laid aside to receive some other trinket newly devised by the fickle-headed tailors, who covet to have several tricks in cutting, thereby to draw fond customers to more expense of money. . . . And as these fashions are diverse, so likewise it is a world to see the costliness and the curiosity, the excess and the vanity, the pomp and the bravery, and finally the fickleness and folly, that is in all degrees, insomuch that nothing is more constant in England than inconstancy of attire." Stubbes was a satirist, and Harrison a plain historian; the following quotation is from Camden, the most learned scholar of the age: "In these days [1574] a wondrous excess of Apparel had spread itself all over England, and the habit of our own country, though a peculiar vice incident to our apish nation, grew into such contempt, that men by their new fangled garments, and too gaudy apparel, discovered a certain deformity and arrogancy of mind whilst they jetted up and down in their silks glittering with gold and silver, either imbroidered or laced. The Queen, observing that, to maintain this excess, a great quantity of money was carried yearly out of the land, to buy silks and other outlandish [foreign] wares, to the impoverishing of the commonwealth; and that many of the nobility which might be of great service to the commonwealth and others that they might seem of noble extraction, did, to their own undoing, not only waste their estates, but also run so far in debt, that of necessity they came within the danger of law thereby, and attempted to raise troubles and commotions when they had wasted their own patrimonies; although she might have proceeded against them by the laws of King Henry VIII and Queen Mary, and thereby have fined them in great sums of money, yet she chose rather to deal with them by way of command. She commanded therefore by proclamation, that every man should within fourteen days conform himself for apparel to a certain prescribed fashion, lest they otherwise incur the severity of the laws; and she began the conformity herself in her own court. But, through the untowardness of the times, both this proclamation and the laws also gave way by little and little to this excess of pride, which grew daily more and more unreasonable."The contemporary drama contains innumerable allusions to the extremity of fashion. "Apparel's grown a god." (Marston's What You Will, iii. 1.) "Poor citizens must not with courtiers wed Who will in silks and gay apparel spend, More in one year than I am worth, by far." (Dekker's Shoemaker's Holiday, ii. 1.) "O, many have broke their backs with laying houses on 'em." (Henry VIII) This magnificent extreme obtained in all ranks of life, as Harrison says, from the courtier to the carter. The only difference was that the rich man dressed in more expensive stuffs; he wore diamonds and rubies where the poor man wore beads of coloured glass. He bought clothes oftener than the poor man; yet people were all alike in this; they dressed as fine and finer than their pockets would allow. The kind of dress worn upon any occasion was not dependent upon the time of day. A man would appear at court in his gaudiest clothes, whether the time was day or night, morning or afternoon. The garments were stiffened and stuffed till the wearer could not move with any comfort. A man in full dress was laced from head to foot. His doublet was laced or buttoned in front. The sleeves were often laced to the arm-holes. The doublet was laced to the hose. The hose was laced. Sometimes even the shoes were laced. A man could not dress himself without assistance. Fashionable dressing, or "making-ready," was such a formidable undertaking that, once accomplished, a man was glad to keep the same clothes on his back all day long. Women carried dress to an even greater extreme than men. They put on a complete framework of whalebone and wire before they began to assemble the outer garments. When the process was completed, all resemblance to a human figure had disappeared. Women were wide and round, stiff and rigid as if made of metal, and their dress abounded in straight lines and sharp angles. What women achieved by means of wire and bone, men accomplished by means of wadding. Wool, hair, rags, and often bran, were used to pad out the doublet and hose. A writer in 1563 (Bulwer, Artificial Changeling) tells a story of a young gallant "in whose immense hose a small hole was torn by a nail of the chair he sat upon, so that as he turned and bowed to pay his court to the ladies, the bran poured forth as from a mill that was grinding, without his perceiving it, till half his cargo was unladen on the floor."

Holme in his Notes on Dress (Harl. 4375), relates the following: "About the middle of Queen Elizabeth's reign, the slops, or trunk hose, with peascod-bellied doublets, were much esteemed, which young men used to stuff with rags and other like things to extend them in compass, with as great eagerness as women did take pleasure to wear great and stately verdingales; for this was the same in effect, being a sort of verdingale breeches. And so excessive were they herein, that a law was made against them as did stuff their breeches to make them stand out; whereas when a certain prisoner (in these times) was accused for wearing such breeches contrary to law, he began to excuse himself for the offence, and endeavoured by little and little to discharge himself of that which he did wear within them; he drew out of his breeches a pair of sheets, two table cloths, ten napkins, four shirts, a brush, a glass, a comb, and night-caps, with other things of use, saying: your lordships may understand that because I have no safer a storehouse, these pockets do serve me for a room to lay my goods in; and though it be a straight prison, yet it is a storehouse big enough for them, for I have many things more yet of value within them. And so his discharge was accepted and well laughed at: and they commanded him that he should not alter the furniture of his storehouse, but that he should rid the hall of his stuff, and keep them as it pleased him." Female extravagance in dress was proverbial: "Not like a lady of the trim, new crept"The women," says Stubbes, "when they have all these goodly robes upon them, seem to be the smallest part of themselves, not natural women, but artificial women; not women of flesh and blood, but rather puppets or mawmuts, consisting of rags and clouts compact together." Out of doors a woman wore little or nothing upon her head. There were several kinds of light hoods, some of which were attached to the collar of the gown, as the "French-hooded cloak." The more common custom, however, was to throw a light scarf or veil over the head. Cypress, a light, gauzy material, was often used for the purpose. (See Middleton's No Wit, No Help, ii. 1.) "A cypress over my face, for fear of sun burning." A mask was always worn by ladies. Masks were made of silk, as a rule, and were either pinned or tied. They were of all colours: black, however, was most popular. People of high social rank often built the hair into towering masses on the crown of the head; but as a rule the hair was dressed plain, though frequently covered with jewels. The Elizabethan women, as well as the men, dyed their hair, not to conceal the fact that it was turning gray, but to please a passing fancy. There was no attempt to conceal the practice, nor was the same colour always used. In fact, the colour of the hair was made to harmonise with the garments worn upon any particular occasion. Those who did not care to dye their hair wore wigs. The Elizabethans revelled in wigs. The Records of the Wardrobe show that Elizabeth possessed eighty at one time. Mary Stuart, during a part of her captivity in England, changed her hair every day. So usual was this habit, and so great the demand for hair, that children with handsome locks were never allowed to walk alone in the London streets for fear they should be temporarily kidnapped and their tresses cut off. That was also a day of face washes and complexion paints. "The old wrinkles are well filled up, but the Vermillion is seen too thick." (Middleton's Old Law, iii. 1.) "Thou most ill-shrouded rottenness, thou piece made by a painter and a 'pothecary!" (Philaster, ii. 4.) "But there is never a fair woman has a true face." (Antony and Cleopatra, ii. 6.) It was also common to paint the breast. ( See Jonson's Malcontent, ii. 3; Middleton's Anything for a Quiet Life, v. 1; Marston's Antonio and Mellida, Part II. iv. 2.) Men wore hats of all sizes, shapes, and colours. The most popular material was velvet. All sorts of feathers were used by men to decorate their hats; black feathers eighteen inches or two feet in length were in great demand. A common decoration was a twisted girdle next the brim, called a cable hat-band. Some hats, however, were perfectly plain, of soft felt. Others wore velvet caps with a jewelled clasp. Occasionally small mirrors were worn in the hat for novelty. The place for the hat was frequently upon the head; but quite as often the hat was worn dangling down the back at the end of a brightly-coloured ribbon. It was worn in either place, either within or without doors. The hair was usually cut short, with, however, a love lock left long behind one or both of the ears. It was adorned with pretty bows of ribbon. Men painted the face quite as frequently and as carefully as the women. The moustache was sometimes left very long. Hair, moustache, and beard were coloured as fancy prompted. The following from A Midsummer Night's Dream is to be understood quite literally: "Either your straw-coloured beard, your orange tawny beard, your purple ingrain beard, or your French crown coloured beard, your perfect yellow." "Forsooth, they say the king has mew'd [moulted] all his gray beard, instead of which is budded another of a pure carnation colour, speckled with green and russet" (Ford's The Broken Heart, ii. 1.) Harrison writes: "Neither will I meddle with our variety of beards, of which some are shaven from the chin like those of the Turks, not a few cut short like the beard of the Marquise Otto, some made round like a rubbing brush. . . . Therefore if a man have a lean, straight face, a Marquis Otto's cut will make it broad and large; if it be platter like, a long slender beard will make it seem narrower. . . . Some lusty courtiers also, and gentlemen of courage do wear either rings of gold, stones, or pearl, in their ears, whereby they imagine the workmanship of God not to be a little amended." Harrison does not mention the fact that gallants usually wore the love lock as an especial support for ladies' favours. Stubbes writes in 1583: "They, the barbers, have invented such strange fashions of monstrous manners of cuttings, trimmings, shavings, and washings, that you would wonder to see." He mentions the French cut, the Spanish, Dutch, Italian, the new, the old, the gentleman's, the common, the court, and the country cuts. He concludes with: "They have also other kinds of cuts innumerable; and therefore when you come to be trimmed they will ask you whether you will be cut to look terrible to your enemy, or amiable to your friend; grim and stern in countenance or pleasant and demure, for they have divers kinds of cuts for all these purposes, or else they lie." Is it, then, any wonder that such words as fool, wretch, ape, and monkey, were then used as terms of endearment! Motto, the barber, in Lyly's Midas, says to his boy: "Besides, I instructed thee in the phrases of our elegant occupation, as, 'How, sir, will you be trimmed? will you have your beard like a spade, or a bodkin? a penthouse on your upper lip, or an alley on your chin? a low curl on your head, like a bull, or a dangling lock like a spaniel?'"

What made the ruff so conspicuous was its size. When first introduced it was modest and unpretentious; but nothing upon which fashion in those days once took a fair hold could remain "confined within the modest limits of order." We hear of ruffs that contained eighteen or nineteen yards of linen. The fashionable depth was one-fourth of a yard. Sometimes they were as much as one-third of a yard deep. Imagine the head of a man or woman, like the hub of a cartwheel, firmly gripped in the midst of a mass of starched linen extending a foot on all sides! So cumbersome were these articles of dress that it became necessary to underprop them with a framework of wire to keep them from tumbling down of their own weight, and to prevent them from dragging their wearer's head down with them. What a stiff, unnatural carriage the habit of wearing ruffs gave to the upper half of the body is fully illustrated by the following: "He carries his face in's ruff, as I have seen a serving man carry glasses in a cypress hatband, monstrous steady for fear of breaking." (Webster's White Devil, ii. 4.) One's head in the midst of such a ruff was free to move, of course, only within limits. In fact, people found it most difficult to eat and to drink. In France, for this fashion was imported from Paris, where it was carried to an even greater extreme than in England, we read of a royal lady who found it necessary to take soup out of a spoon two feet long. In the latter part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth the garment that ultimately supplanted the ruff became popular. The falling band, like the ruff, was made of linen, but less elaborate, not so large, and unstarched. Bands, as distinguished from falling bands, were often starched, as may be seen in the Droesheut engraving of Shakespeare. It was the lack of starch that gave rise to the peculiar name of falling band. It fell close to the neck over the narrow collar of the doublet. A falling band that reached to the edge of the shoulder was unusually large. They were frequently made of, or decorated with, the finest lace. A reason for their popularity is glanced at in The Malcontent (v. 3): "You must wear falling bands, you must come to the falling fashion; there is such a deal o' pinning these ruffs, when the fine clean fall is worth all; and, again, if ye should chance to take a nap in the afternoon your falling band requires no poting [poking] stick to recover his form." The upper part of a woman's body was cased in a neat, tightly-laced bodice, that followed the contour of the body with a fair resemblance to nature. This, however, was the only part of the figure that retained any of its native semblance. The bodice frequently projected downward in a long sharp point over the abdomen; and was often open towards the top to show the breast, or the stomacher of brightly coloured silk beneath crossed laces. The corresponding garment for men was the doublet. It was usually padded and stuffed till quite twice the size of the natural body. The doublet was cut and slashed in front and sides as to show the gay-coloured lining of costly material. It was sometimes laced, but was more frequently buttoned up the front. Two or three buttons at the top were left open and the shirt of delicate white lawn pulled out a little way. This has become the open vest and necktie of our own time. The doublet sometimes projected downward in front, when it was called a peascod bellied doublet; sometimes it surrounded the hips like a short skirt. The sleeves were generally removable and laced to the doublet at the arm-holes. Working people, who, of course, wore doublets, or jerkins, that were but slightly padded, frequently did without the sleeves altogether, the arms covered by the sleeves of the shirt. A pair of drawstrings working in opposite directions at the small of the back enabled one to tighten or loosen one's doublet at will. There used to be a punishment in use in the Colony of New York by which a man was compelled to walk about encased in a barrel; his head projecting from one end, his feet from the other. The Elizabethan women did not carry a barrel about their hips, but they carried a corresponding bulk. What would correspond to a skirt in our time was then called a farthingale. This name, however, was properly applied to the framework of whalebone and wire which the woman buckled on before she began to dress. It clamped her tightly about the waist and was absolutely rigid. One style gave a curve from the waist-line downward; the other style extended level from the waist, and met the vertical line of drapery at right angles. In either case the nether garments were supported by this structure much as we support the week's wash on a rotary drier. The appearance of a fashionable woman when fully dressed was not unlike the colonial culprit in his humiliating barrel; save that the farthingale reached to the floor and was richly bedecked with jet, beads, strings of pearl, jewels, and gold thread. The women of that day thoroughly understood the art of tight lacing. Some of the old pictures of a woman with a wasp-like waist and a huge farthingale look very much like a tin soldier soldered to his base. In 1563 a law was passed in France to limit farthingales to an ell, about four feet, in diameter; and the satirists tell us that in this respect the English outdid their rivals across the Channel. The Scotch farthingale was a variety that was smaller and closer fitting. "Is this a right Scot? Does it clip close and bear up round i" Fine stuff, i' faith; 'twill keep your thighs so cool, and make your waist so small." (Marston's Eastward Ho, i. 2.) "Bumrolls" were a sort of "stuffed cushions used by women of middling rank to make their petticoats swell out in lieu of the farthingales, which were more expensive." (Nares.)

A slop was the common name for a padded hose, and was also applied to wide loose breeches, as were the names, Dutch slop, gaskins, and gally-gascoyns. Gamashes was a name applied to a sort of loose outside breeches worn over the other garments, usually as a protection in travelling. Stockings, or nether hose, were usually of silk and gartered at the top below the knee. They were worn of all colours, and were padded only when necessary to improve the shape of the leg. The shoes of this period were of various shapes and of many colours. They were frequently slashed below the instep in order to show the colour of the stocking. At parting, Ralph, in The Shoemaker's Holiday (i. 1), gives Jane a pair of shoes "made up and pinked with letters of thy same." Hamlet speaks of "provincial roses in my razed shoes." "Provincial roses" refers to the habit of wearing roses, or rosettes, upon the instep. They were generally made of lace, and often decorated with gold thread, spangles, or even jewels. At times the roses were worn large — four or five inches in diameter. "Why, 'tis the devil; I know him by a great rose he wears on's shoe to hide his cloven foot." (Webster's White Demi, v. 3.) Corks, so often referred to in the old plays, were shoes with cork soles that increased in thickness towards the heel, where they might be two or three inches thick. Their purpose was the same as high heels, and, when more fully developed, became known by another name. "Thy voice squeaks like a dry cork shoe." (Marston's Antonio and Mellida, Part I. v. 1.) The chopine was a device used by women principally for the purpose of increasing their height, and to keep their embroidered shoes and farthingales out of the dust and dirt when they walked abroad. The chopine was an expansion of the high heel cork; though, in its extreme fashion, it is better described as a short stilt. The shoe was fastened to the top of the chopine, which was frequently a foot high. The fashion came from Venice, where the height of the chopine corresponded roughly to the rank of the wearer. Persons of very high rank have been known to wear chopines eighteen inches high. The Venetian women so dressed could not walk alone, but required the assistance of a staff, or were led about upon the arm of an assistant, constable-fashion. There is a line in one of the old plays to the effect that when a woman walks on chopines she cannot help but caper. Buttons were then in frequent use, but not so common as to-day. They were small when used upon the front of the doublet, but in female attire they were generally large. One of the most popular styles consisted of buttons covered with silk. They were also occasionally made of brass or of copper, and upon occasions, bore jewels set in gold. We even hear of diamond buttons. The laces by which so many parts of the dress were fastened together were tagged at the ends with "points." These points were frequently of gold, handsomely engraved, and carved. Jewelry of all sorts was in common use, including earrings, hat and shoe buckles, broaches, gold chains, rings, bracelets, garter-clasps, watches, etc. Rings especially were much worn by both sexes. It was a common custom to engrave on the inside a line or two of sentimental poetry, called the posy. It is to this fashion that Hamlet refers in the words, "Is this a prologue or the posy of a ring?" Fans came into use in England for the first time in the reign of Elizabeth. They dangled from the girdle by a silk cord or a gold chain. They were often handsomely decorated with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, agate, and feathers. Fans were not used by men till later times. Gloves were worn, perfume was used, and handkerchiefs were elaborate and costly. The dress of the common folk was like fashionable dress except that it was of cheaper material and did not run to such extremes. It was common then for persons of different ranks and of different trades to reveal the fact by the manner of their dress. Thus the long blue gown was the especial badge of a servant, and the London flat cap of the apprentice. Because of the Reformation, that swept away so many Romish customs, the dress of the clergy was less distinctive than in former times. The armour of this period was an attempt to copy in metal the ordinary fashionable dress. The helmet was decked with enormous plumes. A ruff frequently surmounted a steel corselet. The plates of the body armour were grooved, embossed, and engraved from top to bottom in imitation of embroidery and folds of drapery. Liveries, too, were common. Many trades and societies of London possessed their distinctive dress. The retainers of the great noblemen always wore a badge containing their master's coat-of-arms. This badge, or cognisance, was worn upon the left sleeve.

How to cite this article:_________ Related Articles

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.

When one thinks of costume in the age of

Elizabeth one naturally thinks of three details

as most characteristic: the ruff, the huge-padded hose, and the farthingale. Of these three, the

first is the unique feature of the dress of that particular age. Ruffs of our own time convey no

idea of what was meant by a ruff in 1600. During the time of the early Tudors, partelets, or

narrow collars of divers colours, generally made of velvet, were much worn by the nobility. These

began to grow in size and popularity during the reign of Elizabeth. As was usual in those days,

the new fashion was introduced by the men, but the women were quick to follow in the adoption

of the ruff. Ruffs were made of linen, often decorated with gold and silver thread, and adorned with jewels. They were expensive garments, and could be worn but a few times. In 1564, a woman became the great benefactor of

English society. This woman was a Mrs. Dingham, wife of a Dutch coachman in the service of the Queen. Mrs. Dingham brought to England the art of starching. The use of starch gave the ruff a new birth. It could now be worn more than

once; and, in a trice, the garment was within the reach of all. Elizabeth wore her ruffs closed in

front, extending close under her chin; most women, however, who had fairer skin and shapelier necks, preferred to wear the ruff open in front. The ruff was made of linen, much plaited, and starched stiff, usually with white starch. For a

while yellow starch was fashionable, but the fad was of short duration. Starch was also occasionally used of other colours. Stubbes tells us that the women used "a certain kind of liquid matter which they called starch, wherein the devil hath

willed them to wash and die their ruffs well; and this starch they make of divers colours and hues

— white, red, blue, purple, and the like; which, being dry, will then stand stiff and inflexible about

their necks." In Middleton's The World Tost at

Tennis we find the following stage direction: "Music striking up a light, fantastic air, the

five starches. White, Blue, Yellow, Green, and Red . . . come dancing in." There was a great

revival in the popularity of yellow starch in 1615 due to the fact that an infamous woman, a Mrs. Turner, wore bands so starched at her execution at Tyburn. A long and interesting note on this

occasion is found in Hazlitt's Dodsley, Albumazar (ii. 1). After having been washed, the ruff was

got up with a hot iron and a "poking stick" till it stood out a marvel to behold.

When one thinks of costume in the age of

Elizabeth one naturally thinks of three details

as most characteristic: the ruff, the huge-padded hose, and the farthingale. Of these three, the

first is the unique feature of the dress of that particular age. Ruffs of our own time convey no

idea of what was meant by a ruff in 1600. During the time of the early Tudors, partelets, or

narrow collars of divers colours, generally made of velvet, were much worn by the nobility. These

began to grow in size and popularity during the reign of Elizabeth. As was usual in those days,

the new fashion was introduced by the men, but the women were quick to follow in the adoption

of the ruff. Ruffs were made of linen, often decorated with gold and silver thread, and adorned with jewels. They were expensive garments, and could be worn but a few times. In 1564, a woman became the great benefactor of

English society. This woman was a Mrs. Dingham, wife of a Dutch coachman in the service of the Queen. Mrs. Dingham brought to England the art of starching. The use of starch gave the ruff a new birth. It could now be worn more than

once; and, in a trice, the garment was within the reach of all. Elizabeth wore her ruffs closed in

front, extending close under her chin; most women, however, who had fairer skin and shapelier necks, preferred to wear the ruff open in front. The ruff was made of linen, much plaited, and starched stiff, usually with white starch. For a

while yellow starch was fashionable, but the fad was of short duration. Starch was also occasionally used of other colours. Stubbes tells us that the women used "a certain kind of liquid matter which they called starch, wherein the devil hath

willed them to wash and die their ruffs well; and this starch they make of divers colours and hues

— white, red, blue, purple, and the like; which, being dry, will then stand stiff and inflexible about

their necks." In Middleton's The World Tost at

Tennis we find the following stage direction: "Music striking up a light, fantastic air, the

five starches. White, Blue, Yellow, Green, and Red . . . come dancing in." There was a great

revival in the popularity of yellow starch in 1615 due to the fact that an infamous woman, a Mrs. Turner, wore bands so starched at her execution at Tyburn. A long and interesting note on this

occasion is found in Hazlitt's Dodsley, Albumazar (ii. 1). After having been washed, the ruff was

got up with a hot iron and a "poking stick" till it stood out a marvel to behold.

The nether garment for men was called the hose. Its size was likewise carried to a ridiculous extent. The man, however, laboured under an additional disadvantage. Instead of spreading himself out with whalebone, he gained his

volume by padding. It was from this garment that the poor fellow, already described, took out

his table cloths, napkins, sheets, and other household goods. The hose, which was laced to the doublet, was of different lengths. The French hose, or trunk hose, was short and full-bodied, reaching less than halfway between the hip and

knee. The gaily hose was long, and reached almost to the knee. The Venetian hose reached below the

knee to the place where the garter was tied. "The French hose," says Stubbes, "are of two divers

makings, for the common French hose (as they list to call them) containeth length, breadth, and

sideness sufficient, and is made very round. The other containeth neither length, breadth, nor sideness (being not past a quarter of a yard side) whereof some be paned, cut, and drawn out with

costly ornaments, with canions annexed, reaching down beneath their knees." Canions were ornamental rolls that terminated the hose above the knee, a fashion imported from France. They are

noted in Henslowe's diary among the properties

of his theatre. Thus, under April, 1598, he pays for "a pair of paned hose of bugle panes drawn

out with cloth of silver and canyons to the same." He also notes "a pair of round hose of panes of

silk, laid with silver lace and canons of cloth of silver." Paned hose consisted of hose in which

pieces of cloth of different texture or colour were inserted to form an ornamental pattern; or of

hose slashed to show the lining or the garment beneath. "He [Lord Mount joy] wore jerkins and

round hose . . . with laced panes of russet cloth." (Fynes Moryson.) "The Switzers wear

no coats, but doublet and hose of panes, intermingled with red and yellow, and some with blue,

trimmed with long cuffs of yellow and blue sarcenet rising up between the panes." (Coryat's

Crudities.)

The nether garment for men was called the hose. Its size was likewise carried to a ridiculous extent. The man, however, laboured under an additional disadvantage. Instead of spreading himself out with whalebone, he gained his

volume by padding. It was from this garment that the poor fellow, already described, took out

his table cloths, napkins, sheets, and other household goods. The hose, which was laced to the doublet, was of different lengths. The French hose, or trunk hose, was short and full-bodied, reaching less than halfway between the hip and

knee. The gaily hose was long, and reached almost to the knee. The Venetian hose reached below the

knee to the place where the garter was tied. "The French hose," says Stubbes, "are of two divers

makings, for the common French hose (as they list to call them) containeth length, breadth, and

sideness sufficient, and is made very round. The other containeth neither length, breadth, nor sideness (being not past a quarter of a yard side) whereof some be paned, cut, and drawn out with

costly ornaments, with canions annexed, reaching down beneath their knees." Canions were ornamental rolls that terminated the hose above the knee, a fashion imported from France. They are

noted in Henslowe's diary among the properties

of his theatre. Thus, under April, 1598, he pays for "a pair of paned hose of bugle panes drawn

out with cloth of silver and canyons to the same." He also notes "a pair of round hose of panes of

silk, laid with silver lace and canons of cloth of silver." Paned hose consisted of hose in which

pieces of cloth of different texture or colour were inserted to form an ornamental pattern; or of

hose slashed to show the lining or the garment beneath. "He [Lord Mount joy] wore jerkins and

round hose . . . with laced panes of russet cloth." (Fynes Moryson.) "The Switzers wear

no coats, but doublet and hose of panes, intermingled with red and yellow, and some with blue,

trimmed with long cuffs of yellow and blue sarcenet rising up between the panes." (Coryat's

Crudities.)